You are hereFlight Planning / International Operations

International Operations

How to Cross Borders

by John T. Kounis

[Note: The article that appears here was the Flying Tips article published in the Fall 2003 issue of Pilot Getaways. As such, some information may be outdated.]

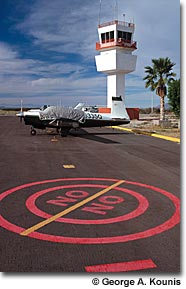

I vividly remember the excitement of my first international flight. Although it was just a 20-minute jaunt across the U.S.–Mexico border, I had been apprehensive weeks in advance. But the actual crossing was mundane. The engine kept droning along, oblivious to the fact that we were now in foreign airspace. That’s when it became clear that flying internationally is simply a matter of a little bureaucracy, and is well worth the effort.

Flight Planning

Prior to your flight, double-check the documents that you normally carry: airworthiness certificate, aircraft registration (but not a temporary “pink slip”), operating limitations, weight and balance, pilot certificate, and current medical. To fly in foreign airspace, you’ll also need a radio station license for the airplane and a radiotelephone operator license for yourself. To get them, submit three FCC forms (159, 160, and 605), along with a $50–$100 fee. You can download the forms from the FCC’s website and even apply online, (202) 418-0680, wireless.fcc.gov/aviation.

If you have modified your airplane with long-range fuel tanks, carry a copy of your FAA form 337. Also, if you’re flying a rental airplane, have the registered owner give you a letter authorizing you to take the airplane out of the country. It’s a good idea to have the letter notarized.

Insurance

Check the territorial limits of your insurance policy before your trip. My insurance policy states that I am covered “in the United States and its territories and possessions, Canada, Mexico, the Bahama Islands, or while en route between these places.” This means that I am covered if I crash in the Dominican Republic en route to Puerto Rico, but not if I’m landing in the Dominican Republic.

As long as you are within the territorial limits of your policy, proof of insurance through a U.S. company is accepted in most countries, except in Mexico, where the government requires liability insurance through a Mexican company. MacAfee & Edwards can sell you a short-term Mexican insurance policy for a single trip as well as annual and fleet policies, (213) 629-9777 or (800) 334-7950, www.macafeeandedwards.com. If you’re making multiple trips to Mexico, Baja Bush Pilots offers their members a $110 annual Mexican liability policy, (480) 730-3250, www.bajabushpilots.com.

Leaving the U.S.

The United States does not require you to land at an airport of entry (international airport) prior to exiting the country. You are required to make a declaration if you are carrying more than $10,000 in “monetary instruments,” (travelers checks, cash, money orders, etc.). You may also want to declare any valuable items, like jewelry or electronics, to avoid problems when you bring them back. The best way to make this declaration is to land at an airport of entry in the United States on your way out and visit the customs office. I like to do this anyway, because I often meet the customs officers who will clear me on my return flight.

Crossing the Border

A flight plan must be activated for all international flights. If you’re flying to Mexico, the Bahamas, or the Caribbean, you’ll cross the Air Defense Identification Zone, or ADIZ, that runs along the eastern, southern, and western borders of the U.S. (marked on the sectional chart with a red line bordered by red dots). To cross the ADIZ, you must file an IFR or a Defense VFR (DVFR) flight plan. On a DVFR flight plan, you have to notify ATC of the estimated time, position, and altitude of ADIZ penetration at least 15 minutes in advance. A call to flight service usually suffices for this notification. You’ll likely receive a discreet transponder code to squawk while you are in the ADIZ (mode C is required). Aircraft on IFR flight plans will already be in contact with ATC, so there are no special reporting requirements.

In addition, all aircraft in an ADIZ must have tail numbers at least 12” high. Temporary numbers are acceptable; I use duct tape.

Entering a Foreign Country

The first landing in a foreign country must be at an airport of entry; it is the pilot’s responsibility to notify customs officials there prior to arrival. For arrivals in Canada, the procedure is simple. Call (888) CAN-PASS before departure and inform them of your airport of entry and estimate d arrival time. Notification must be made no less than two hours before landing and can be made up to 48 hours in advance. You’ll be asked for your call sign, the names of all people on board, and their birth dates and citizenship. If you arrive earlier than your ETA, be prepared to wait in the aircraft for inspectors to arrive. Once you’ve landed in Canada, if you’re not met by a customs inspector, call (888) CAN-PASS and you’ll receive your customs authorization over the phone.

d arrival time. Notification must be made no less than two hours before landing and can be made up to 48 hours in advance. You’ll be asked for your call sign, the names of all people on board, and their birth dates and citizenship. If you arrive earlier than your ETA, be prepared to wait in the aircraft for inspectors to arrive. Once you’ve landed in Canada, if you’re not met by a customs inspector, call (888) CAN-PASS and you’ll receive your customs authorization over the phone.

Most countries require one-hour advance notice for customs. For Mexico and the Bahamas, you can request flight service to notify customs at your destination by indicating “ADCUS” in the remarks section of your flight plan. The notification is made when you activate the flight plan, not when you file. If your flight is one hour or less, call the customs office at your destination before takeoff to assure at least one-hour notice. Finally, carry proof of citizenship for all crew and passengers. A passport works best, although a certified copy of your birth certificate along with photo id is acceptable. Permanent residents should carry their U.S. Alien Registration Card (green card) for re-entry into the United States.

Flying in a Foreign Country

Once you’re in a foreign country, you’ll need to understand the procedures specific to that country. As long as your aircraft is registered in the United States, you won’t need a foreign license to fly it. Since the U.S. adopted the ICAO standard airspace designations (e.g. Class B instead of TCA), foreign airspace is usually easy to understand. Rules for most classes of airspace are similar, although some countries designate special use airspace as Class F, which is not used in the U.S. Other flight regulations range from no VFR night flying (in Mexico) to a requirement to file a flight plan for all flights longer than 25 nm (in Canada). The AOPA International Operations page has a summary of key regulations for nearby countries (see below).

In most countries, an ICAO flight plan form is used instead of the abbreviated form U.S. pilots recognize. To familiarize yourself with the form, you can view a copy online at www.faa.gov/ats/aat/IFIM/7233_4.pdf.

Returning to the U.S.

Most countries require you to land at an airport of entry and clear exit customs before leaving the country. Usually, you’ll have your passport stamped and may pay a departure tax. Canada is a notable exception. You can leave Canada from any airport, international or not.

Your first landing in the United States must be at an airport of entry or a landing rights airport. Both are international airports. An airport of entry (AOE) typically has a regular customs office, so you only need to provide advance notice of arrival. Most landing rights airports (LRA) have no customs office on the field, so you have to secure permission from the customs officer to clear there. Generally, permission is granted if a customs officer is available to come to the field and meet your flight. Most flights from the south can only clear customs at one of 31 designated airports along the southern border; you must land at the one closest to where you enter the U.S. The list of these airports is published in the U.S. Customs Guide for Private Flyers; you can access it by clicking on a link at www.cbp.gov/xp/cgov/travel.

U.S. Customs requires at least one-hour advance notification of your arrival, and fines for inadequate notice are steep—typically $5,000 for the first violation. Although you can request “ADCUS” on your flight plan, it is safer if you notify customs yourself. It’s worth paying for the phone call from abroad. Look up the U.S. Customs Office telephone number for your airport of entry in Flight Guide by Airguide Publications or the “International Landing Facilities” section of the AOPA Airport Directory, or call Flight Service. Make sure to write down the time you called and the name of the officer who noted your ETA.

From the south, you will also need to contact flight service or ATC en route at least 15 minutes prior to crossing the ADIZ for a squawk code.

Land as close to your schedule as possible, but do not land before your ETA. In order to ensure an accurate arrival time, I plan for a slow ground speed to allow for delays and headwinds. Then I can slow down and even S-turn to assure an on-time arrival. After landing, stay with the airplane until the customs inspector comes to the aircraft.

There is a $25 annual fee for U.S. Customs. The first time you pay the fee, you receive a decal good for the rest of the calendar year. One year, my poor planning resulted in having to pay the fee at 4 p.m. on December 31.

Additional Resources

The members-only section of the AOPA website has a wealth of information on international flying, from short cross-border trips to Canada or Mexico, to over-water flights across the Caribbean or the Atlantic, (800) USA-AOPA, www.aopa.org/members/pic/intl/. The FAA’s International Flight Information Manual is also a useful resource, www.faa.gov/ats/aat/IFIM/ifimccql.htm. The Baja Bush Pilots conducts group trips to Mexico and Central America; there is a wealth of information about flying south of the border on their website, (480) 730-3250, www.bajabushpilots.com.