You are hereVOR & Glideslope Checks

VOR & Glideslope Checks

More Than Just a Good Idea

by Crista V. Worthy

When I first met my husband Fred, he’d been a pilot for decades, but hadn’t flown in years. I expressed a big interest in flying, so he took refresher courses, got current, and then we rented a Cessna 172 and flew a short day trip along the coastline. The next trip in the same aircraft was flown at night from Santa Monica Airport (SMO) to Las Vegas, a trip my husband had made numerous times in the past. I knew nothing about any of the instruments, but he explained to me that we were using the VORs to navigate (this was in 1995). After a couple of hours aloft, he commented that we should be seeing the glow of the city ahead, and yet, we saw nothing but blackness as we hummed over the desert. Finally he said, “You know, we are lost. The VOR must not be operating correctly.” He called up ATC; they found us on radar and gave us vectors toward the city. After half an hour, we saw the glow of lights behind the mountains and landed uneventfully.

We flew home during daylight via the infamous IFF system (I Follow Freeways, in this case Interstate 15), and when we returned the aircraft, we told the FBO what had happened. The owner, a former Pakistani Air Force pilot who went by the name of—no kidding—Roger, said, “Oh yes, the VORs in that airplane are highly unreliable.” Gee, it might have helped if he’d told us that before we departed. I won’t even go into the other squawks we found on that flight (other than the inspection plate that fell off the wing halfway home). Soon thereafter, we bought a Cessna 210.

I was doing my best to learn as much about flying as possible by reading aviation books and magazines, and paying attention when we flew. One day as we climbed out above the runway, I said, “I’ve noticed a lot of airports have a big compass painted on the tarmac off to the side somewhere. Why? Is it so you know which way is north when you’re over the airport? Isn’t that what your compass and DG are for?” He laughed and replied, “No, that’s called a compass rose. It’s to help you check your compass for accuracy. It points correctly to north, so you taxi up onto it and check to see that your compass is accurate. At SMO, people also do their VOR checks on it; those are required every 30 days for IFR flight.” My reply: “Why haven’t we done that?”

Busted.

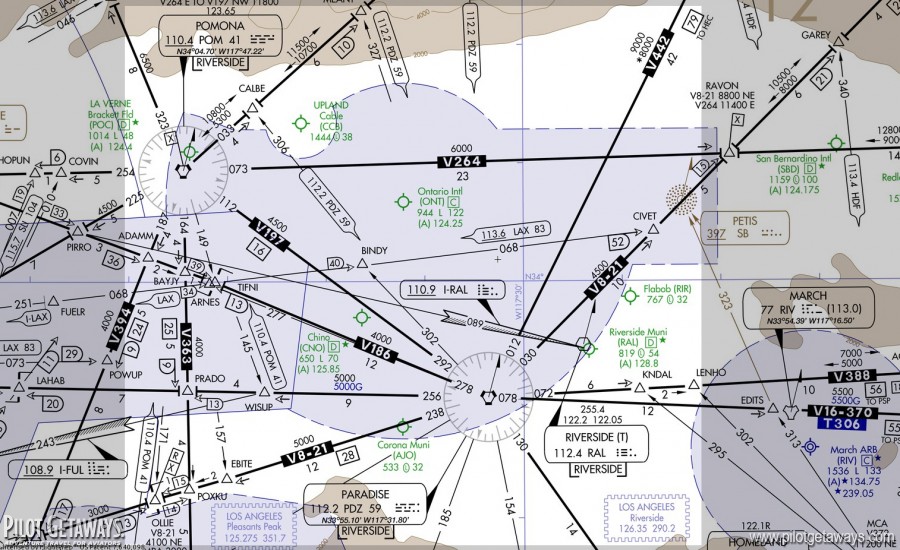

FAR 91.171, the “VOR Check” rule, says you can’t use your VORs for IFR flight unless they’ve been checked within the last 30 days and are accurate to within plus or minus four degrees. When you come in to SMO on the VOR-A approach, the VOR is just off the west end of the runway. If you break out just above minimums for Runway 21 and your VOR is five degrees off, it’s not going to make much difference. But how about the VOR/DME Rwy 7 approach to Colorado’s Craig-Moffat Airport (CAG)? As you hit the final approach fix (FAF), where the Maltese cross is, you’re supposed to be at or above 7,900 feet MSL and you’re 15 DME from the reference VOR, Hayden (CHE). Passing the FAF, you can drop down to the minimum descent altitude (MDA), 10.5 DME and 7,220 feet MSL. However, you’ll pass by a couple of obstacles on your right, one as high as 6,963 feet MSL. (The runway elevation is 6,193 feet.) And if you miss, there’s another obstacle just barely off your right at 7,010 feet MSL. If your VOR is off, you could be dangerously close to some of these, particularly if you got a little sloppy on the descent. Remember, VOR course deviation is determined by degrees of error. The farther away you are from the VOR, the more off-course you are, all with the same deviation indication. At 15 DME, one degree of error puts you about a quarter-mile off course. At 10 DME, one degree of error puts you about 1,000 feet off course. It’s easy to see how you could potentially fly right into an obstacle if your VOR is several degrees off on an approach like this.

If you have two VORs, you can use one to check the other, as allowed per FAR 91.171(c). If one is off by a few degrees (legal) and you use it to check the other, your second VOR could be off by as many as eight degrees and still be legal. On a different VOR approach, you might use that second VOR to initiate a descent and could easily begin your descent too soon, putting you hundreds of feet too low. Out of the primary protected airspace on a VOR approach, a little low, with no visibility is not a good set of circumstances. So take the time to check your VORs. You never know when your GPS may decide to take the day off. It’s happened to me in a Cessna 185, and it’s happened to me in a Boeing 767—no, I wasn’t flying it, and they lost everything except their compass—so it can happen to you.

It’s easy to understand why we need to check our VORs. What about your glideslope? There you are, descending through the clag, trusting your life to this instrument. Amazingly, you aren’t legally required to test your glideslope ever. But now that we’ve mentioned it, wouldn’t you feel better knowing yours is accurate? Here’s an easy way to check it: Choose an ILS approach to fly. As you brief the chart, find the altitude in fine print above the Maltese cross. This isn’t the glideslope (GS) intercept height (although occasion- ally that will coincide). Remember, on an ILS, the FAF is close to where the GS intersects the minimum intermediate segment altitude (the lightning bolt). The Maltese cross FAF is for the non-precision localizer approach. But the GS altitude verification occurs at this point. The glideslope crossing height is depicted on the approach plate. This is the altitude you should see when you cross the FAF with your GS centered. And, if your GS is not centered at the indicated altitude, you have a problem and should avoid using your GS until you find out whether the error is in your indicator, your altimeter, or the airport’s glideslope transmitter.